Based on coverage from CBC and Nunatsiaq news.

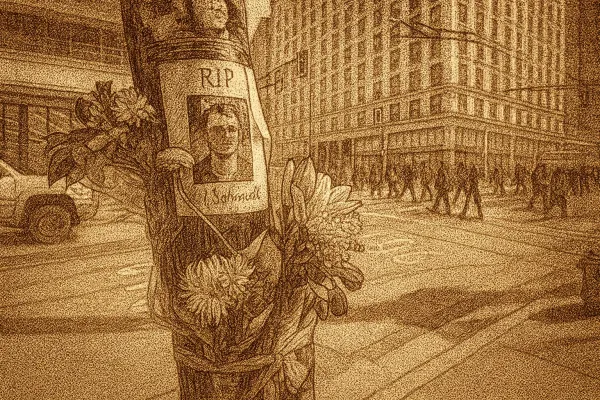

In the serene yet isolated community of Pond Inlet, Nunavut, a series of tragic events this past summer has cast a long shadow. Three young lives were lost to suicide in a short span, leaving families and the community grappling with grief and searching for answers. The tragedy struck close to home for Verna Strickland, who lost a 13-year-old relative. Just days before his death, he was joyfully helping prepare for a wedding, a stark reminder of the hidden struggles many face.

The statistics are sobering. From 2010 to early 2024, 451 Inuit in Nunavut died by suicide. Young people, those 19 and under, accounted for nearly a quarter of these deaths in recent years. The suicide rate in Inuit Nunangat is estimated to be five to 25 times higher than the rest of Canada, a crisis that has prompted the Nunavut government to repeatedly declare suicide a public health emergency.

In response to the recent tragedies, the community of Pond Inlet has seen an outpouring of support. Organizations like the Canadian Red Cross and the Pulaarvik Kablu Friendship Centre have stepped in, offering not just counselling but also community-building activities like rock painting and healing circles. These efforts have provided some solace and a sense of connection during a time of profound loss.

Tununiq MLA Karen Nutarak highlighted the swift response from the territorial government, which she believes prevented further tragedies. Resources were mobilized quickly, with some youth being sent out of the community for counselling due to a lack of local resources. Others were placed on mental health watch, a precautionary measure that underscores the severity of the situation.

Nunavut's Health Minister, John Main, acknowledged the urgency of the crisis, stressing that the government's response must go beyond mere words. Initiatives are underway, including a $5 million package aimed at suicide prevention, which will fund men's group programming and education on the safe storage of firearms and medication. Main emphasized that suicide prevention is a complex issue requiring a multifaceted approach, involving not just health professionals but the entire community.

The federal government has also taken notice. During a recent visit to Iqaluit, federal Health Minister Marjorie Michel expressed concern over youth suicide rates in Nunavut and pledged to work with the territorial government on new youth programs. Meanwhile, Nunavut NDP MP Lori Idlout plans to raise these issues with federal leaders, advocating for more culturally appropriate counselling services that incorporate Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit, traditional Inuit knowledge.

Despite these efforts, the path forward remains challenging. Strickland voiced a sentiment shared by many in the community: frustration with systems that feel disconnected from Inuit ways of life. "We're losing our children and we're losing our future," she lamented, capturing the urgency and heartbreak that permeates Pond Inlet.

As the community continues to heal, the hope is that these tragedies will spur lasting change. The need for culturally sensitive support and sustainable mental health resources is clear. While there are no easy solutions, the collective resolve to address this crisis is a step toward ensuring that the young lives lost are not forgotten, and that future generations can grow up in a world where hope and resilience prevail.