This report is based on multiple sources, including news articles, public records, official documents, and community input. While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, some details may be disputed or evolving. For corrections, please contact info@thecanadareport.ca.

*if you wish to donate to the GoFundMe set up by the local residents, you can find it here

The morning the valley pushed back

By the morning of April 17, the steps outside the Columbia Shuswap Regional District headquarters in Salmon Arm had filled with protesters from Silver Creek and Yankee Flats. Farmers, retirees, and young families stood together, their frustration carried on hand-painted placards and in conversations about odour, water, and accountability. They had come for a single vote on a single motion, but for them it was the culmination of years of tension over a composting business once welcomed as a solution, now seen by many as a neighbourhood problem.

Inside, the directors took their seats. Area D Director Dean Trumbley, who said he had fielded two years of calls, emails, and meetings about the issue, reminded the board what was at stake. “This is a very complex issue that has heavily divided an amazing community,” he said. “I am asking for the board to support the decision of staff. But the caveat on this is understanding that this is not a vote against Spa Hills. This is a vote on the current state of what it’s in.”

Outside, protester Pat Peebles called the facility’s growth “a gradual escalation to a disaster.” Standing with her, Brittany Moore accused both the CSRD and the province of letting the operation “run wild.” Another resident, Russ McCann, questioned how a business could be allowed to operate without sufficient enforcement staff.

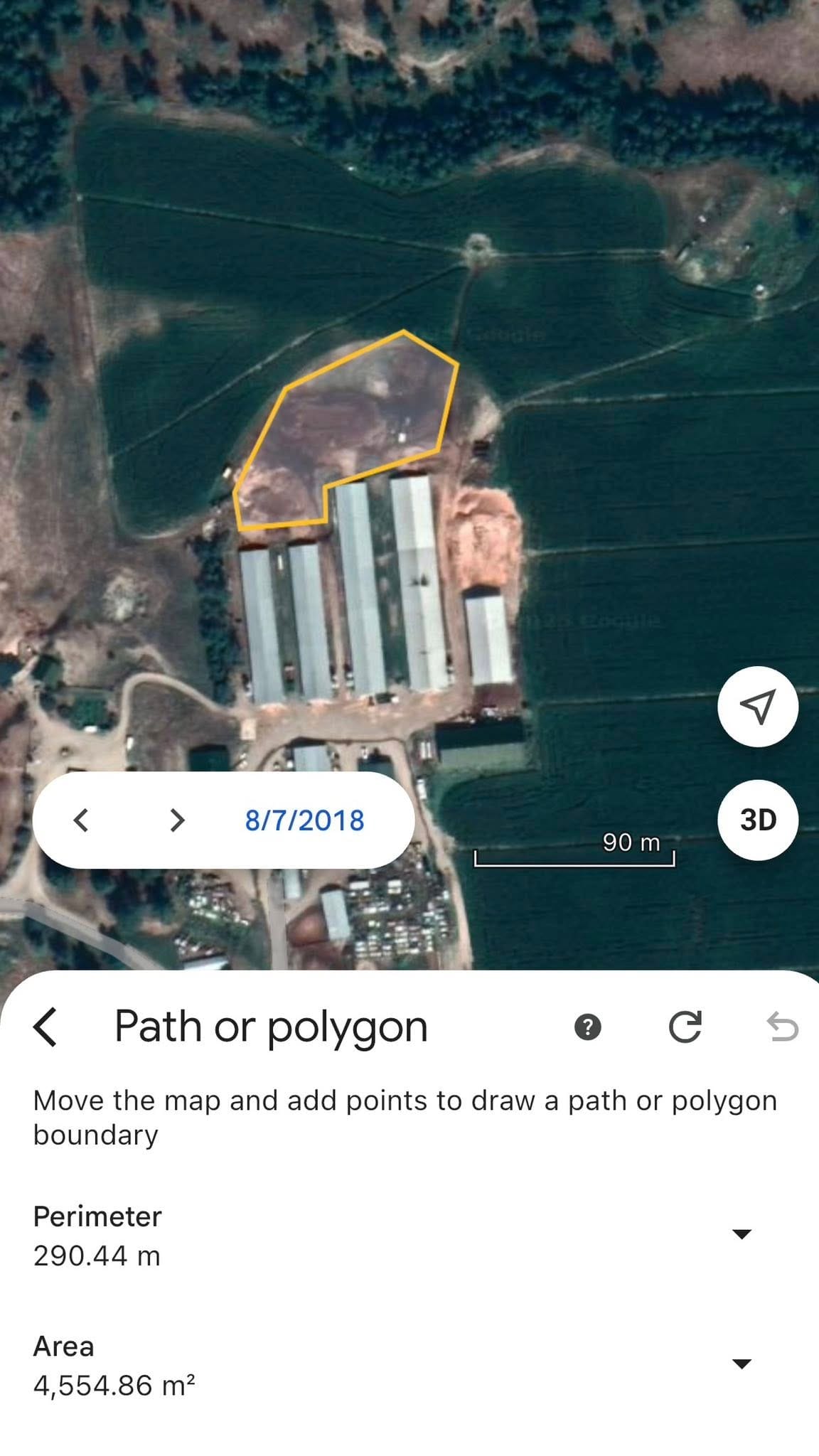

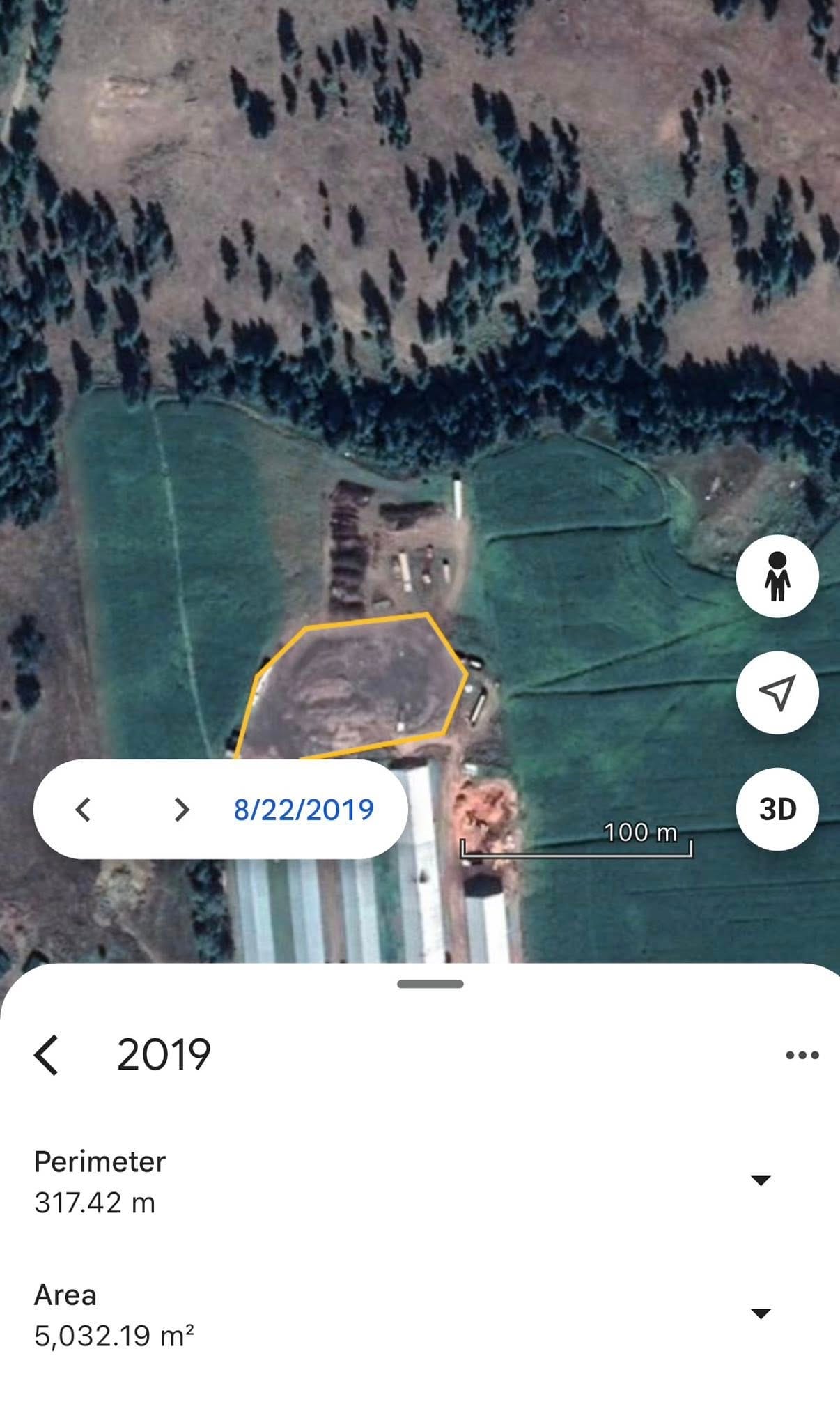

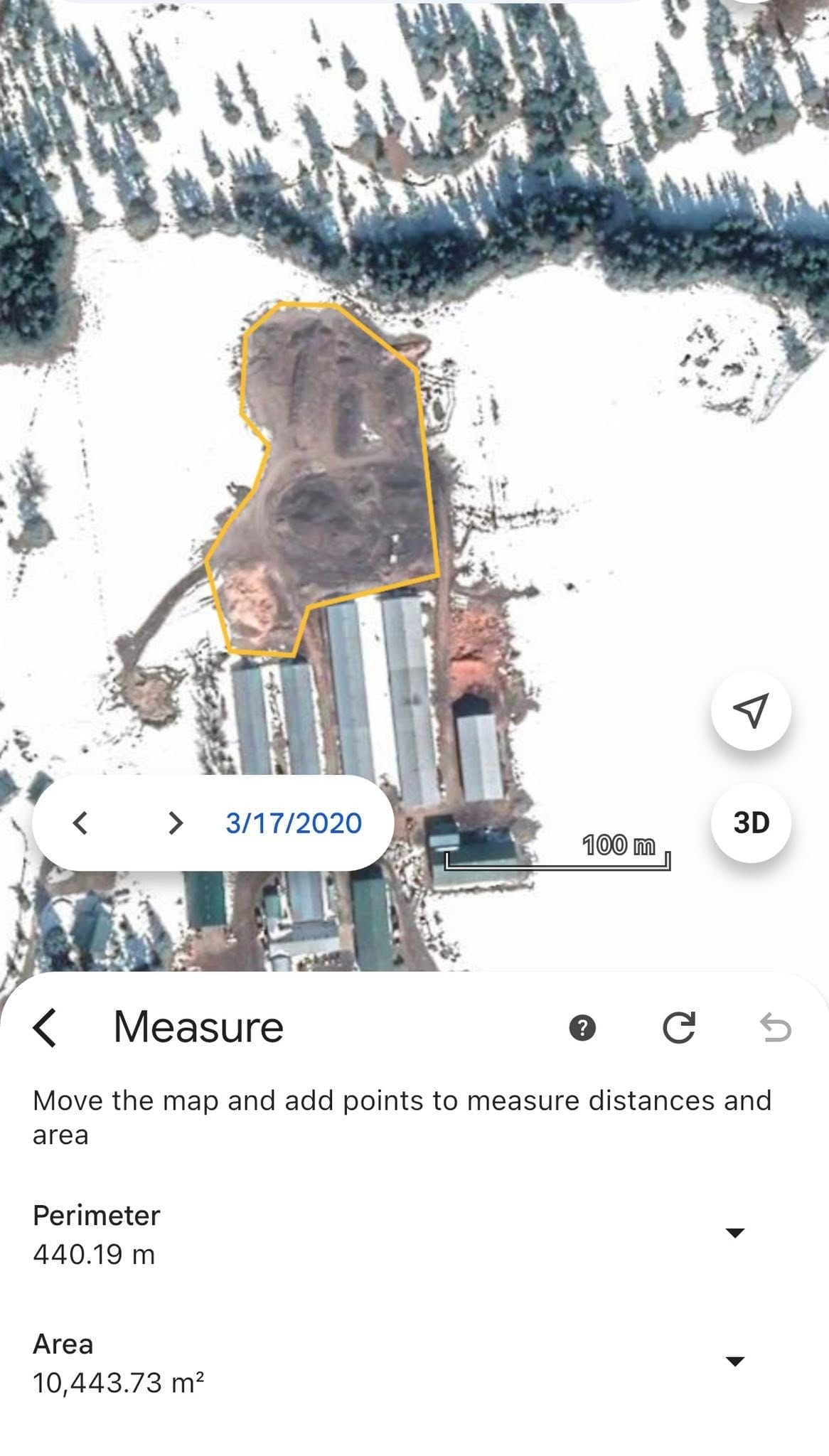

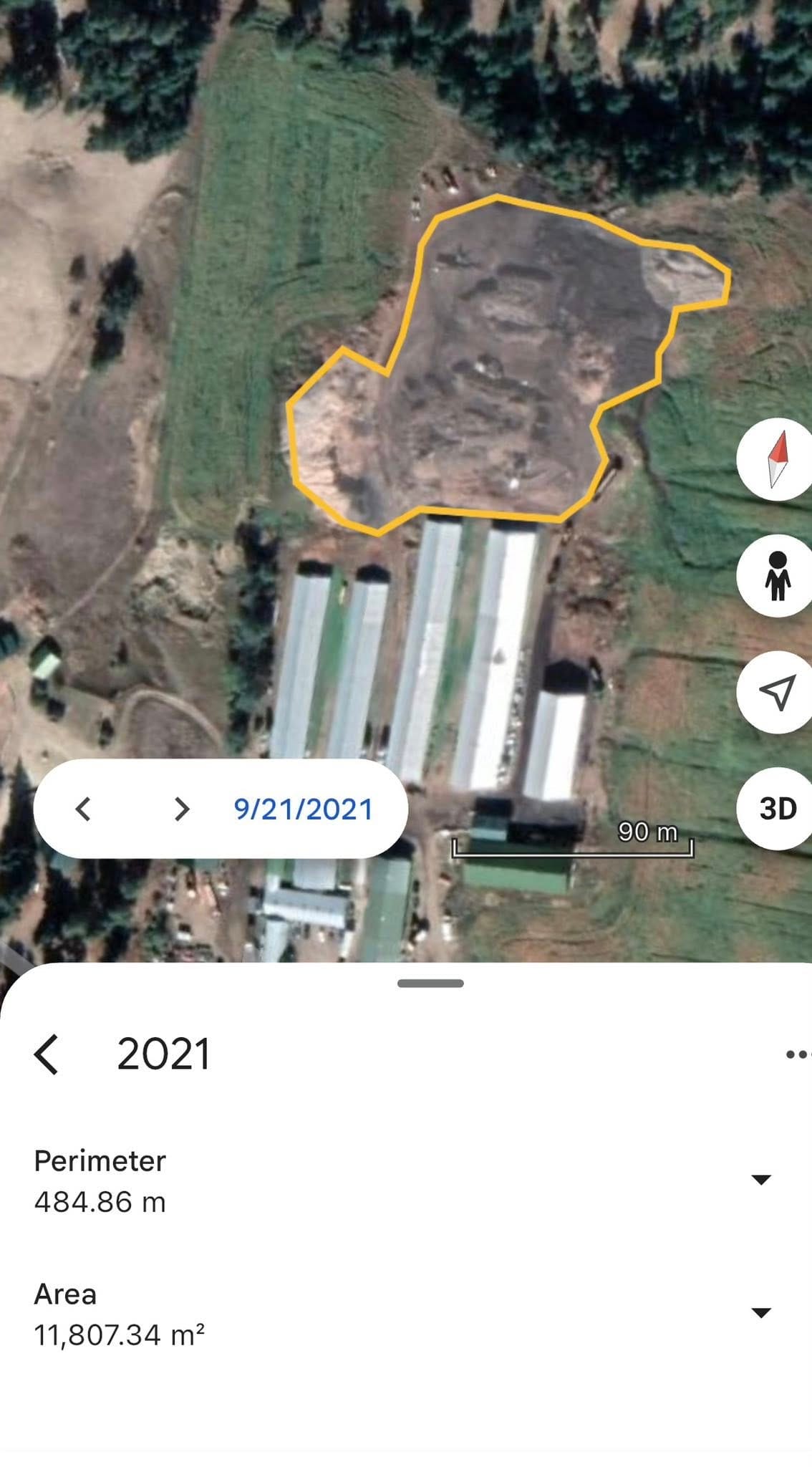

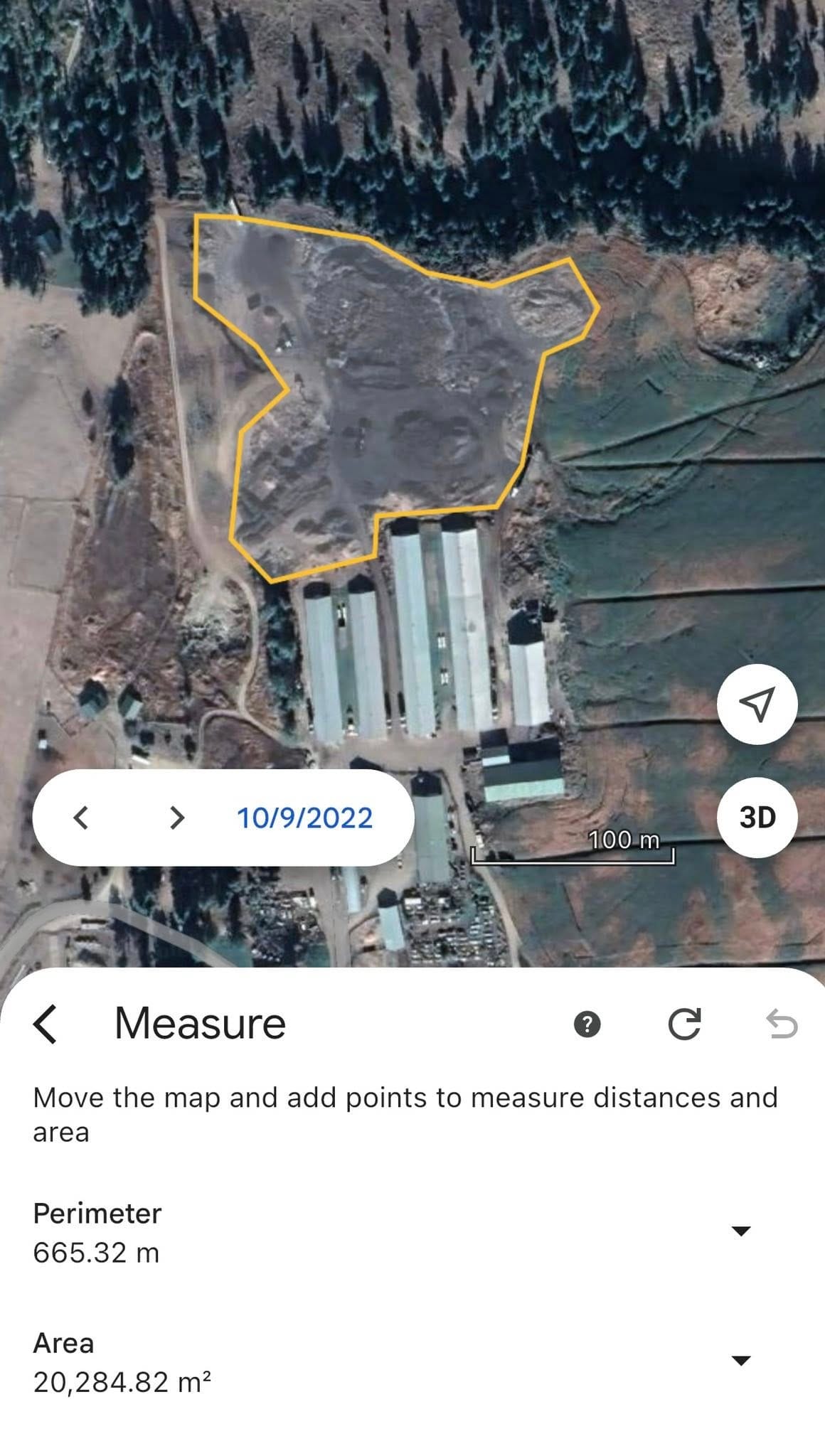

The motion before the board looked technical. Spa Hills Compost, operating on Yankee Flats Road in the Salmon Valley, had applied to change its zoning so that the area on its parcel used for primary composting and curing could match the real-world scale of its business. The land-use bylaw allows up to 500 square metres of primary composting area on the rural-zoned site. Spa Hills asked to legalize 23,725 square metres. The request amounted to formal approval for an operating footprint nearly fifty times larger than what zoning allowed. The directors voted unanimously to deny first reading. In the gallery, the protesters exhaled, then applauded. They had won a vote. They had not won an ending.

How a small composter grew past the map lines

When Spa Hills launched more than a decade ago, it was part of a wave of small operators encouraged to pull organics out of the waste stream. The idea aligned with a province-wide push to extend the life of landfills by diverting food scraps and meat trimmings into compost. The Salmon Valley land-use bylaw was amended to allow composting on the rural property where Spa Hills sits, even as the region tightened rules elsewhere in the district. In practice, that created a bespoke permission: a compost facility could exist on Yankee Flats Road, but the operational constraints would be strict.

The bylaw set out that no more than 500 square metres could be used primarily for composting and curing. That cap makes sense on paper. It was meant to contain outdoor piles and keep the messy, odorous parts of the process limited and manageable near homes and small farms. But as Spa Hills scaled up its service, the environmental and regulatory architecture did not scale with it. Restaurants, butcher shops and farm operations from the North Okanagan and into Kamloops turned to the company to move their organic waste. Spa Hills told the CSRD board in an October 2024 letter that it was providing a green solution, keeping organics out of landfill, and investing heavily in research and improvements to meet government standards. The company also emphasized its local payroll. “We currently provide full-time employment for 13 individuals and part-time employment for an additional 5 individuals,” the owners wrote.

Neighbours do not dispute that the service is needed. In fact, they share the wider worry that landfills are filling fast. The point of rupture is proximity and scale. As the volume of slaughterhouse byproducts, food waste and manures increased, the site’s physical footprint ballooned. Piles that had once been manageable mounds became long windrows. Trucks grew larger and more frequent. The neighbours say the smells changed too, from earthy compost to what they describe as raw putrefaction. The scale drifted past what local zoning envisioned, and the systems meant to control the mess, from odour to leachate, did not keep up. In that gap sits the conflict that exploded into view this spring.

The ask that hardened a community line

Spa Hills’ application was blunt in its logic. The owners were already operating across roughly 23,725 square metres, and the regional district’s own shift to organics diversion had made composting more central to waste-management planning. Formalize the footprint, they argued, and they would keep investing in improvements to meet standards. They highlighted a plastic-removal system as evidence of reforms already made, saying their device pulls film and fragments out of incoming waste and reduces contamination to a tiny fraction. In a short interview earlier this year, co-owner Josh Mitchell said a “special device” removes plastic, addressing all but 0.3 percent of contamination, and that new inventions continue to appear. “We have made major improvements and things are looking better,” he said. He told one local paper that compost is processed to 55 C or higher to kill pathogens and that specified risk materials such as heads and spinal columns go directly to the landfill per provincial rules.

The staff report that went to the board in April did not quarrel with the usefulness of composting. Planner Laura Gibson simply concluded the site, at this scale, was incompatible with the neighbourhood. “Staff are recommending that the board deny first reading, because the subject property’s proximity to nearby rural properties and their single detached dwellings is not suited to the current scale of composting facility,” she wrote. Area C Director Marty Gibbons captured what several directors had seen and smelled from their car windows: “Spa Hills is in contravention of the bylaw; what they are doing is not permitted and negatively affects their neighbours. I have driven through there and the smell is horrendous.”

In the end, directors who still view composting as essential sided with the staff recommendation. “There are things that need to be taken care of in our communities,” said Area F Director Jay Simpson, “and it’s important that we don’t have to export byproducts to other communities. But I agree that the current state of Spa Hills is well beyond what was originally anticipated.” The unanimous vote left Spa Hills with a stark choice: find a way to operate within 500 square metres or face the consequences of a bylaw-enforcement process already in motion.

What the neighbours describe, day after day

Even before the board meeting, the neighbourhood mood had shifted from pleading to mobilizing. A GoFundMe launched this winter to raise money for legal advice and an environmental expert. As of midsummer, residents said roughly 40 households had submitted victim impact statements, describing odours, illness and disrupted lives. “Some residents are experiencing headaches and runny noses, feeling nauseous,” said resident Deneen Tomlinson. Brittany Moore told a reporter that winter brought no relief. “We’re locked inside our house, and guess what? You can’t even open a window because the smell is in your house for hours.”

The most unsettling complaints involve birds. Neighbours have documented flocks of crows and gulls moving between the site and nearby properties, sometimes dropping meat scraps onto lawns and pastures. “I’ll be outside and I’ll be doing my horses, and there’ll be a full flock of crows flying around my property,” said Moore. “And they’re wrestling over a piece of meat that gets dropped in my yard.” Vectors are more than a nuisance in composting. They are a red flag that the initial phase of processing is not contained and that animal tissue is accessible to scavengers.

Residents have tried to quantify what they fear may be contaminating water. A petition submitted to the CSRD included claims that testing by CARO Analytical found extremely high E. coli and coliform counts in an aquifer near the site. This spring, locals also reported finding phthalates in a deep well north of the facility and traces in the Salmon River. Phthalates are used to soften plastics and are under study for endocrine disruption. None of these findings have been publicly validated by provincial authorities, and Interior Health told residents it would wait for Ministry of Environment results. But the crude fact of location is undeniable: the Salmon River runs directly below the facility. If leachate escapes uncollected from compost piles, it has only gravity to obey.

Inspectors arrive, reports trickle out

The provincial file on Spa Hills has two distinct chapters. Early inspections and data reviews in 2019, 2020 and 2021 found the operation complied with B.C.’s Organic Matter Recycling Regulation, which governs how compost is made and managed. That changed in 2024. In January, an environmental protection officer conducted an on-site inspection in response to complaints and issued a non-compliance advisory. Advisories are the low end of the enforcement spectrum. They signal an expectation of timely fixes without heavy penalties. By July, a second inspection yielded a warning letter citing several areas of non-compliance under OMRR. Among the most serious findings were failures to store residuals in a way that limits vector attraction and a storage area that lacked a leachate collection system, resulting in liquids discharging to ground.

Spa Hills told the inspector it was building a lined pond to capture leachate from the storage area so that it could be recycled back into the composting process. The company already had a 4,500 litre collection system for leachate in receiving, curing and processing areas. But the gaps were material. Liquids observed leaving the storage area were entering the environment. The Ministry gave operators 30 days to correct deficiencies.

In May 2025, the Ministry conducted another inspection. The official report was not immediately posted, but residents say the document, later shared with them, contained a stark conclusion: the effluent observed being introduced into the environment at the facility was considered a waste under the Environmental Management Act. According to that report, ammonia in the sampled effluent exceeded provincial water-quality guidelines for aquatic life by roughly 400 times. The letter, residents say, ordered Spa Hills to immediately cease the discharge of waste effluent to ground. The implications ripple downhill. Ammonia is acutely toxic to fish at elevated concentrations, and the Salmon River supports species that matter to the region’s ecology and the culture of nearby First Nations.

The Ministry will not discuss details while its compliance work is ongoing. “The Ministry conducted a site inspection in May and is working towards completion of the inspection report,” a spokesperson said in early July, noting that inspection records are posted to the province’s enforcement database once issued to the regulated party. It is not just that residents want answers. They want to see what enforcement looks like when repeated warnings do not change what they smell, see and report.

Inside the smell: vectors, pathogens and plastics

Composting is chemistry made visible. Piles of organic matter warm as microbes break down proteins, fats and carbohydrates. Properly managed, oxygen and moisture are balanced, heat rises past 55 C to kill pathogens, and the mass is turned to maintain aerobic conditions. An earthy smell is expected. Hydrogen sulphide and ammonia are warning signs that the pile is going anaerobic or that nitrogen-rich materials are pushing the process past its comfort zone. If animal byproducts are not fully incorporated or covered, vectors arrive. If piles sit on bare soil or unlined pads, leachate can seep into ground. If the operator takes in plastics and does not remove them, fragments can persist in the finished compost.

Spa Hills acknowledges the risks and says it has engineered away much of the problem. Mitchell told local media the facility uses high heat to clear pathogens, and he claims the “Class A” compost curing outside is not leaking liquid. He says a device now pulls most plastic from the stream before composting. The neighbours are unconvinced, and the material evidence on the ground has not helped. Social media posts have circulated images residents say show plastic film and fragments in stockpiles and on fields where material was spread. A resident who worked on a farm below Spa Hills described “animal carcass bits” dropped by birds and a smell that made her dry heave.

The health anxieties are not idle. The community’s GoFundMe warns that if temperatures are too low during the cooking phase, bacteria such as Salmonella can survive, and that off-gassing includes ammonia and hydrogen sulphide. Residents also point to the risk of pharmaceuticals used to euthanize horses entering the compost stream. Spa Hills counters that only two small abattoirs supply material, that specified risk materials are landfilled, and that euthanasia drugs are the same class of anaesthetics used in surgery and are broken down at high temperatures. At the heart of the debate is proof: clear, independently verified data on what is going into the piles, what temperatures and retention times are achieved, and what leaves the site in air and water. Without that, the conversation collapses into cross-claims measured in odour and fear.

The company’s case, and the costs of saying no

Spa Hills’ owners rarely comment now, citing active work with the Ministry of Environment and the CSRD. When they do, the message pivots to improvements and the public service they provide. The company takes in organic waste otherwise bound for landfill, composts it into a soil amendment, and uses much of it on a farm that grows feed crops. The jobs are real in a community with few large employers. Directors themselves acknowledge that composting saves taxpayers money by stretching the life of local landfills and reducing tipping fees and transport costs that would otherwise rise.

All that is true, and it is part of what makes the politics of enforcement so fraught. Denying the zoning amendment did not shut the business. It triggered a different conversation about scale and compliance. If the company can operate within 500 square metres of primary composting area, upgrade its pads and leachate systems, and clamp down on odour and vectors, then the essential service argument regains force. If it cannot, then the local government faces the cost, time and uncertainty of trying to compel change through the courts.

There is also the question of where the waste would go. If Spa Hills is forced to sharply downsize, the organics it processed will need to be handled elsewhere, driving additional truck traffic on other roads and potentially shifting odour and leachate risks to another community. Several directors used their speaking time in April to insist that the answer cannot be simply pushing the problem away. “Spa Hills needs Silver Creek, and Silver Creek and the larger community needs Spa Hills,” Trumbley said. That mutual dependence is now strained by the smell outside kitchens and the photos of birds with meat in their beaks.

A local government with few tools

After denying the amendment, the CSRD issued a short statement that said only this: a bylaw-enforcement plan has been developed and the process is ongoing. Because enforcement involves a legal file, the district will not comment further. Residents have urged the district to write a new composting bylaw with teeth. Staff advised against it, pointing out that without a clear path to enforcement, paper rules create false expectations. Still, Trumbley has publicly pushed for stronger action. “It’s affecting people not being able to sell properties, it’s affecting people’s ability to be able to use their places in the summertime,” he said at a November board meeting. “We have a provincial report that’s come out showing they are out of compliance in a lot of areas.”

What can a regional district do in practice when an operator exceeds what zoning allows? It can issue warnings, tickets and orders, and in cases of continued non-compliance, it can seek an injunction in B.C. Supreme Court to compel a halt or a downscaling. That is exactly what the residents’ lawyer, Angela McCue, urged in a June 25 letter, asking the CSRD to seek an injunction requiring Spa Hills to reduce its production to fit the bylaw footprint. Those steps are invariably considered in camera. They take time. And they cost money that rural governments do not have in reserve. The CSRD’s reluctance to litigate in public is about protecting the integrity of the file. It also reflects the limits of local power when the crux of the problem is environmental compliance that falls under provincial law.

The province’s role, measured in warnings

Under the Organic Matter Recycling Regulation, the Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy is responsible for ensuring compost facilities build and operate systems that control pathogens, odours, vectors, and leachate. The province has inspected Spa Hills multiple times, escalating from advisories to a formal warning in September 2024 and another warning in 2025. The ministry stresses that many odour complaints involve nuisance odours that do not necessarily indicate pollution or harm to human health. It is a true point, but it rings hollow to people who cannot open their windows. If effluent is entering the ground with ammonia orders of magnitude above aquatic standards, the odour debate becomes academic.

The enforcement ladder has more rungs: compliance orders, administrative penalties and court action under the Environmental Management Act. The record so far shows a preference for warnings coupled with an expectation that the operator will fix deficiencies. That approach aligns with the province’s broader regulatory posture, which has long aimed to help businesses come into compliance rather than penalize them out of existence. But the patience of neighbours and local governments has a horizon. When warnings do not produce the promised improvements, the credibility of the regulator becomes part of the story.

Beyond one farm: a made-in-B.C. regulatory gap

This fight in Yankee Flats is not an outlier. Across rural B.C., small composters have been asked to do two things at once: scale up to meet a climate-driven goal of diverting organics, and remain invisible to the people living next door. The province has rules for how compost is made, but odour is only loosely addressed through requirements for best management practices, not a numeric standard that triggers enforcement. Local governments have zoning bylaws but limited capacity to inspect and prosecute. The Agricultural Land Commission regulates land use on farmland, but neighbours say it has not weighed in decisively on whether the current scale of operations at Spa Hills constitutes a non-farm use. Meanwhile, Interior Health is a stakeholder for drinking water risks but defers to the Ministry of Environment for first-instance compliance.

Layer those jurisdictions together and the gaps show. Residents complain to the CSRD, which refers odour and leachate to the province. The province warns and waits for corrections. The CSRD considers bylaw tools but keeps enforcement discussions in camera. Months pass. In that vacuum, rumours flourish. People post photos on Facebook of plastic fragments in piles and cite Global News footage of garbage trucks unloading loads they say are riddled with contamination. The operator points to new equipment and upgraded practices. Without transparent, timely data and joint communications, trust decays.

The lesson is structural: big environmental ambitions, designed at the provincial level, demand enforcement and transparency resources that match the ambition.

Who answers for the mess now

Accountability spreads across three desks. Spa Hills is responsible for operating within its zoning and complying with OMRR. The CSRD is responsible for enforcing its bylaws and ensuring that land use aligns with what was permitted. The Ministry of Environment is responsible for ensuring compost operations meet provincial environmental standards and for acting decisively when they do not. The residents’ file also touches the Agricultural Land Reserve and, potentially, First Nations whose territories include the Salmon River, where consultation records from earlier zoning changes remain a point of contention among some locals.

On the company’s side of the ledger, the question is simple. Can it demonstrate, with third-party verification, that plastic contamination in inputs is removed to a de minimis level, that pathogen kill temperatures and retention times are achieved and logged, that vectors are controlled, and that leachate is fully captured, treated and reused or disposed of lawfully. On the regional district’s ledger, the question is whether it will seek an injunction if the site cannot be reduced to the 500-square-metre primary composting footprint. On the province’s, the question is whether warnings will harden into orders and penalties if inspections continue to find non-compliance.

What comes next for Silver Creek

The board vote in April did not end the odour. Summer arrived with heat that makes any compost operator’s job harder. Residents continue to document what they see and smell. They feel like they are living in a case study of regulatory delay. Spa Hills says it is working with both the CSRD and the province and intends to keep upgrading the site. The Ministry is still writing reports that will either confirm residents’ most alarming claims or put some of them to rest.

There are plausible pathways out of the stalemate. The fastest would be a technical fix: impermeable pads under all active piles, engineered leachate collection and recirculation across the site, improved enclosures for initial mixing, and strict feedstock controls that reject contaminated loads. Transparent public reporting would help, including third-party audits of temperatures, retention times and finished compost quality, and an odour management plan that sets out how complaints are logged and addressed. The slower path is the legal one, where the CSRD asks the court to force the operator to comply with the 500-square-metre limit and the province escalates beyond warnings if leachate discharges continue. The most painful path is no path at all, a holding pattern where neighbours keep their windows shut while paperwork circulates behind closed doors.

On the steps after the April decision, Brittany Moore was clear-eyed about the work ahead. “It is in our favour,” she said, “but there’s still a long road ahead to being able to enjoy your backyard.” She's right. The conflict at Spa Hills is now less about one vote and more about whether the systems meant to protect communities can be made to work when the wonky details of compost turn into odour in a kitchen and foam on a creek. The valley will know the answer not from press releases, but from the first evening someone can leave a window open again without thinking about what is piling up over the hill.

Source 1 | Source 2 | Source 3 | Source 4 | Source 5 | Source 6 | Source 7 | Source 8 | Source 9 | Source 10 | Source 11

Additional source files: