This article is an update to our earlier deep dive which detailed how residents in Silver Creek and Yankee Flats mobilized against Spa Hills Compost this past spring. If you missed that story, here’s the backdrop before the latest twist.

Recap: How We Got Here

Back in April 2025, the Columbia Shuswap Regional District (CSRD) board voted unanimously to deny Spa Hills Compost’s rezoning application. The facility, located on Yankee Flats Road in the Salmon Valley, had asked to expand its permitted composting footprint from 500 square metres to nearly 23,725 — fifty times what zoning allowed.

That decision came after months of mounting pressure from residents, who rallied on the steps of the CSRD office in Salmon Arm with signs reading “Protect our wells” and “No more stink.” Their complaints weren’t abstract. They described overwhelming odours, scavenging birds dropping meat scraps onto their properties, and fears of groundwater contamination.

Provincial inspection reports in 2024 and 2025 added fuel to the fire, citing failures to control leachate and vectors, and one finding that effluent ammonia levels exceeded aquatic guidelines by 400 times. Despite Spa Hills’ claims of investing in upgrades, from plastic-removal systems to lined leachate ponds, neighbours said they saw little change on the ground.

The CSRD’s April vote did not shut the business down. It triggered the next stage: enforcement. The board signaled that if Spa Hills could not operate within the 500 m² footprint, legal action could follow.

The New Development: Legal Action

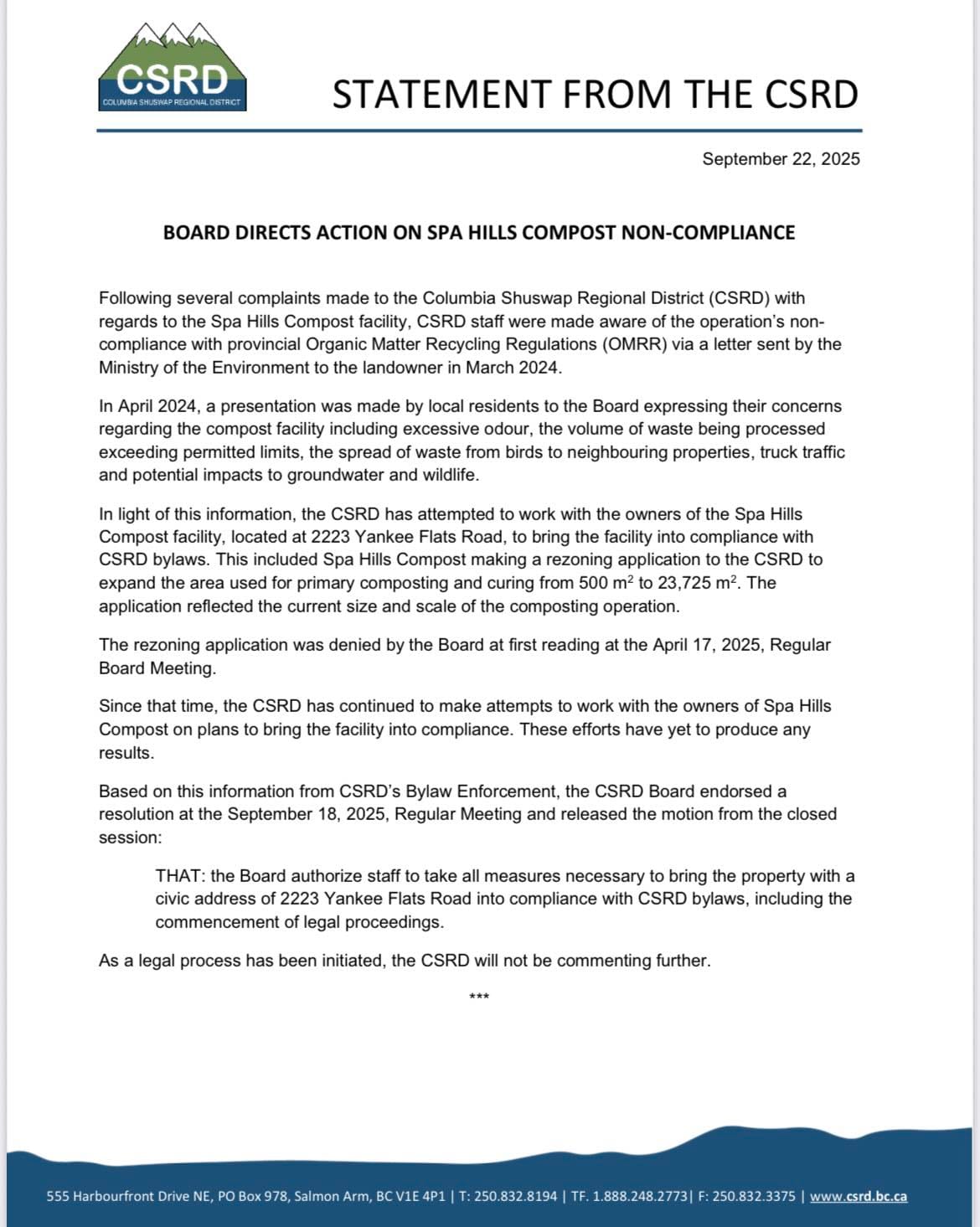

That “next step” has now arrived. On September 18, 2025, the Columbia Shuswap Regional District (CSRD) board voted in a closed session to authorize staff to “take all measures necessary” to bring Spa Hills Compost into compliance with local zoning, including the commencement of legal proceedings.

Four days later, on September 22, the CSRD sent a letter to residents who had filed complaints, confirming the decision. The letter recounted the timeline: complaints stretching back to spring 2024, provincial findings of non-compliance under B.C.’s Organic Matter Recycling Regulation, the rezoning application that sought to legalize a 23,725 m² footprint (nearly fifty times larger than zoning permitted), and the board’s unanimous denial of that request in April 2025.

In the months since that denial, odour complaints persisted and residents accused the CSRD and the province of inaction. Some families even sought legal support from West Coast Environmental Law to push the issue forward. With the September letter, the CSRD signaled it had reached the end of its cooperative approach and was escalating to enforcement through the courts.

The CSRD has gone silent, noting that once legal proceedings are underway, no further public comment will be made.

For Silver Creek residents, the decision feels like long-awaited validation after more than a year of foul air, scattered waste, and unanswered questions about water quality. For Spa Hills Compost, it represents a direct legal challenge to the scale of its operations.

Support The Canada Report and help keep it ad-free and independent — click here before you shop online . We may receive a small commission if you make a purchase. Your support means a lot — thank you.

What’s at Stake

- For residents: Relief from odours, truck traffic, and fears of water contamination that have dominated daily life.

- For Spa Hills: The survival of its current business model. The company processes organics from across the North Okanagan, employs more than a dozen staff, and presents itself as a vital part of regional waste-diversion efforts.

- For the CSRD and province: A precedent. If the courts back enforcement, it could signal how far rural governments can go in compelling compliance when provincial warnings fail.

The Bigger Picture

This update reinforces what we reported in our deep dive: the Spa Hills conflict is bigger than one compost facility. It highlights the cracks between local zoning authority and provincial environmental regulation, and the challenge of advancing ambitious organics-diversion policies without creating neighbourhood flashpoints.

For Silver Creek, the legal filing feels like long-overdue progress. For the region, it is a test case: can waste-diversion goals and community well-being coexist, or will one side always carry the smell of compromise?